Democracy? Make your choice!

11/06/2019 21:39 - Posted by Tom van Leeuwen

In recent centuries the power of governments has become stronger and stronger. The governments got involved increasingly deeper into our lives and the citizens, the individuals, have ever

less to say about ever

more issues.

Climate policy is an excellent example of this interference. The government relies on

completely unreliable data, unproven hypotheses, and ideas while the consequences of this interference affect everyone. At present, governments worldwide are about to make cheap and reliable energy sources -that form the basis of our economic prosperity- inaccessible. The results are far-reaching.

The future of human development is at stake. To what extent does the government have the right to exert such a profound influence on society in general and on the individual in particular?

Here, I want to dive into the concepts of democracy and parliamentary democracy.

Is it morally acceptable that we must resign ourselves to the majority vote, even if we know for sure that that majority is wrong and is endangering our future?

- Is parliamentary democracy democratic?

- Is direct democracy desirable?

- The smaller the better

- A morally acceptable alternative

- Conclusion

1. Is parliamentary democracy democratic?

"Western societies are democratic." That's what we learn at school. But is this actually true?

Democracy is a form of government in which power lays with the people.

According to current definitions, this can be done in two ways: representatively (parliamentary) or directly.

In a parliamentary democracy, every individual can choose a representative who will, during a certain period, exercise power in the name of that individual over the issues that exist within the system.

Three problems within a parliamentary democratic system can result in an individual not being heard about a particular issue or even worse: that his/her power can be used against him/her.

1.- Election Program

The representative represents a large group of individuals who may have different opinions on the issues raised at the time of the election. For example, it is almost inevitable that

the representative will think differently about one or more issues than the individual he/she represents and will, therefore, act against the opinion of that individual the moment he/she exercises power over those issues.

2.- Coalition formation

Furthermore, our representative may have to work together with other representatives to get a majority so that

the elected representative has to adapt his/her position and thus exercise power in a way that does not concord with the opinion he/she pronounced before he/she was elected.

3.- Unforeseen issues

Another problem is that issues arise that did not exist at the time the representative was elected. The individual who chose him/her then depends on the opinion that his/her representative

forms on that new issue. This opinion

can go against the opinion or interests of that individual on that issue.

Does the power lay with the people?

It is clear that in a parliamentary democracy

an individual cannot be certain whether he/she can exert power on all issues that come to vote during a certain period. So the power does not lay with the people, but with their representatives: the politicians. As a result,

parliamentary democracy does not meet the main definition of a democracy: the power lays with the people.

Parliamentary (representative) democracy does not meet the definition of democracy and is therefore not democratic

2. Is direct democracy desirable?

In its ideal form, a direct democratic government system does have none of these objections. Every individual can directly exercise power on every issue that comes up. There are no coalition formations nor government periods, so there is no problem with unforeseen current issues.

The government only consists of executive officials who handle every issue according to the wishes expressed by the majority of the people.

The power remains in the hands of the people and this system, therefore, meets the main definition of democracy.

But there are two problems with direct democracy. In the first place, it is slow and cumbersome because every issue must be submitted to the people.

The second problem is much more serious: Direct democracy is unfair. The fact that a majority wants something does not mean that that opinion is true or justified. The power of the majority can be used to hurt the minority. It is often said: "Democracy is the dictatorship of the majority". The following metaphor illustrates that: "Democracy is like two wolves and a sheep voting on the menu for dinner."

Democracy therefore is morally unacceptable.

Where does the democratic system fail? To find out, we need to see where democracy is applied, the root of the problem.

Democracy is a system for organizing a society. A system to shape collaboration between individuals. The moment these individuals start working together, they

voluntarily give up part of their individual freedom. Every individual must adapt so that the collaboration runs as smoothly as possible. This is a choice that must be made.

But, is this choice made in a

conscious way?

Collaboration

Collaboration is a very important part of human civilization. Without collaboration, much of human progress would have been impossible.

On the other hand, human cooperation also has its dangers. All the wars that have been fought in history would never have taken place without collaboration. Collaboration irrevocably leads to a concentration of power among a small group of people. And precisely these power concentrations lead to monopolistic situations in business and conflicts at an international level.

Collaboration must, therefore, be handled with extreme care and must never be taken for granted.

No one should be forced to collaborate with others without consciously choosing to do so. A democracy is morally unacceptable when every individual is forced to participate and is irrevocably exposed to its outcome.

A child is born within the system. At no time does a child choose whether or not to participate in this system. A social contract is never signed. It is even questionable whether there are legal grounds for forcing someone to pay taxes. No one has ever consciously chosen to be ruled by a parliamentary democratic government.

In a democracy, the power lays with the people and therefore with the individual.

This means as well that every individual must be able to choose not to participate and to withdraw from the system!

3. The smaller the better

The "ideal democracy" would consist of a single person. There would never be disagreements and everyone would be satisfied with the decisions made.

But in this case, there is no collaboration and therefore no need for democracy, so this does not count.

If we go one step further, we come across the smallest real democracy: a marriage. Both spouses

voluntarily give up part of their freedom to continue their lives together. Often it goes well, certainly in the beginning, but sometimes even on this small scale, there are differences of opinion and other problems. Sometimes those problems are so serious that collaboration must be stopped.

On a slightly larger scale, we see a family. Three, four or more people living and working together. In this case, the collaboration is not entered into voluntarily by all individuals. After all, children cannot choose their parents and vice versa.

The problems that arise from a family situation can be more serious than those that occur within a marriage. Brothers can argue with each other. Parents can have problems with their children.

If we continue like this, we come across increasingly larger forms of democratic collaboration: an apartment complex, a sports club, a small village, a city, a province, a country, etc.

The more extensive the partnership, the less influence each individual can exercise on decision making.

This exponentially increases the chances that decisions are made against the opinion or interest of an individual and therefore it also increases the chance of conflicts. So you could argue that a democracy will get worse when applied to larger groups.

And we see that in practice: Smaller countries are often more successful than larger ones in the same geographic area. Andorra is more prosperous than Spain, Monaco is more prosperous than France, Singapore is richer than Malaysia and so on.

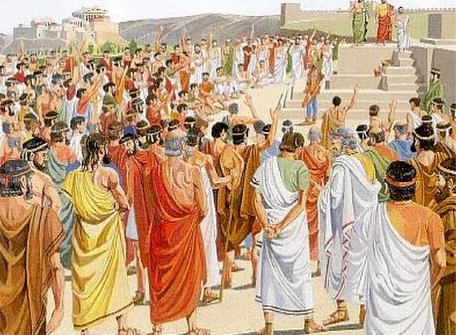

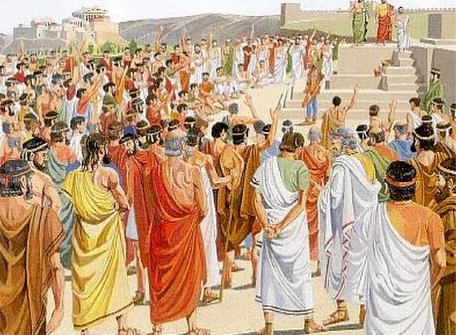

When democracy was first applied in Greece in the sixth century BC, that area consisted of around 200 city-states. Each of those city-states had its own state form. In ancient Athens, there were only 30 thousand people entitled to vote, who were all allowed to address the meeting on their own initiative. That is the size of a small Dutch municipality.

What is now referred to as "democracy", therefore, has virtually nothing to do with the original meaning of the word in terms of form and size.

4. A morally acceptable alternative

Translation note: In its

original version, this part of the article describes the Dutch constitution, but most of the text applies to other countries as well.

The parliamentary democratic models that are currently used in the Western world date from the 19th century. In the Netherlands, for example, the 1848 Constitution lays the foundation for the current administrative system.

What did the world look like in 1848? There was no easy transportation nor communications. The combustion engine dates from 1885 and the earliest forms of telephony came into existence around 1890. In the Netherlands, there was a period of classical economic liberalism, and the government barely interfered with the economy. There was a night-watchman state with minimal taxation. The income tax was only (temporarily!) introduced in 1914. Active voting rights for women have only existed since 1922. Women have therefore never been allowed to vote on this constitution.

In fact, no one now alive voted on this constitution. So this cannot be called democratic in any way to start with.

The Dutch constitution of 1948 can not at all be called democratic because:

- it describes a parliamentary democratic system

- No one currently alive has voted for this constitution

We must look at our constitution, and the parliamentary democratic system described therein, from that point of view. At that time, perhaps a flawed parliamentary democratic system was acceptable; there was simply not much to decide about and there were no technical means available to arrange it differently.

The current reality is completely different. The government has directed

more and more power to itself and is on a large scale involved with issues that individuals can arrange themselves, such as education and healthcare.

Technological progress has made it possible to involve the people much more directly in decision-making.

A morally acceptable system should meet the following requirements:

- Participation is voluntary. Every individual can withdraw him or herself from the system at any time and from that moment on he/she will no longer be exposed to the decisions that are made

- The competence of the system is limited to issues that fall outside the individual responsibilities of each citizen, such as infrastructure (common property management) and military defense

- The system is direct democratic. Every citizen can vote on every proposal

- The system is applied to a geographical area as small as possible

You could think of a system in which there is no compulsory taxation and where paying a voluntary contribution gives the right to indicate -electronically for example- the destination for that contribution. At that same time, other subjects could be voted on.

In such a system, voting is linked to paying the contribution and

the government budget depends directly on the amount the citizens are really disposed to pay for it. Government debt is strictly forbidden.

It might even be possible to have a system with multiple, competing governments. For example, one government could offer more services than the others in areas -such as education, healthcare, or retirement- that do not belong to the government's basic tasks. Each individual can then decide for him or herself in which democratic system he/she wants to participate, or he/she can decide to be completely independent.

Just as in a perfect direct democratic system, such a government consists solely of executive officials who implement the decisions made by the participating individuals.

5. Conclusion

If we really consider

our society and look at the facts objectively,

nothing seems as obvious as usually presented. A lot of things are completely different from what we are taught at school. That's why it is so dangerous to regard the education of our children as a government task.

Parliamentary democracy is undemocratic, the Dutch and most other western constitutions are undemocratic and direct democracy is immoral. Nobody has consciously chosen to be subject to a government.

Regarding climate policy, apart from the scientific issue of whether there is a reason to take action, it is

morally irresponsible that the government in its current form grants itself the right to disrupt the lives of citizens the way it is doing and plans to do in the future.

Tom van Leeuwen, April 2016.

(Adapted for Holoceneclimate.com in November 2019).